MSU Research: Space Radiation as Cyber Tool?

There is always some fascinating research coming out of Montana State University. Check out the latest news below via the MSU News Service.

Story by Marshall Swearingen, MSU News Service

BOZEMAN — Like turning lemons into lemonade, a Montana State University research team hopes to turn the radiation of outer space into a cybersecurity tool that could protect sensitive data transmitted by satellites.

Backed by a $275,000 grant from NASA, the team will design, build and test a device that puts to beneficial use the high-energy particles emitted by the sun and other celestial bodies — radiation that has long been an expensive design concern for NASA.

The idea for the new technology emerged from a decade-long MSU project to develop radiation-resistant space computers that are more affordable than the bulky models used now, according to Brock LaMeres, professor in MSU's Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering. LaMeres is leading both projects.

"We started to ask, 'What if we actually used (the radiation) to our advantage?'" LaMeres said.

In a conventional space computer, it's a problem when radiation particles strike transistors, the tiny electronic switches that are the building blocks of modern computing. Charged radiation particles can randomly open or close the switches, resulting in computing errors, LaMeres explained. The particles are mostly blocked from the Earth’s surface by the planet’s atmosphere.

The new technology is intended to convert those switching events into the random numbers needed for encryption, a process in which data is encoded — and then decoded by its intended recipient — using a key, which could be a long sequence of numbers.

"Truly random numbers are hard to get in outer space," LaMeres said. Currently, satellites use their own software to generate pseudo-random numbers, which determined hackers could crack by detecting patterns. On Earth, random numbers used for encryption are generated, among other ways, by measuring physical events, such as the time between keystrokes on a computer.

In the concept for the new technology, LaMeres explained, transistors are programmed to represent the digits in an encryption key. Any switching caused by radiation particle alters the digits unpredictably, producing a ready supply of truly random keys.

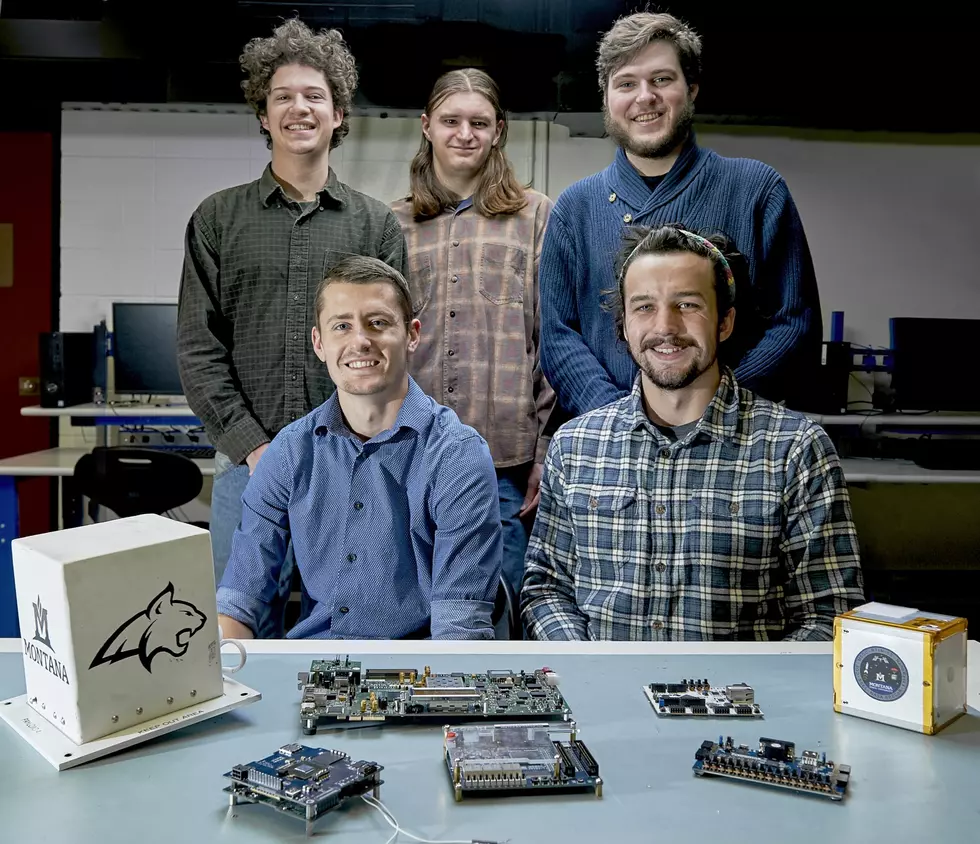

The interdisciplinary MSU team includes five undergraduates in MSU's Norm Asbjornson College of Engineering who will take the computing concept and build the device for their capstone project, which engineering majors complete as a requirement of graduation. All five students also received grants from MSU's Undergraduate Scholars Program to fund additional research that is more than what is expected in a traditional capstone, LaMeres said.

"I'm curious to see what they come up with," said capstone mentor and project manager Trevor Gahl, who is earning his master's in electrical engineering and previously worked on LaMeres's radiation-tolerant computer project. "They have a lot of ideas."

This summer, the MSU students will test the device aboard a high-altitude helium balloon operated by World View Enterprises, an Arizona-based company. The balloon will rise to an altitude of roughly 100,000 feet, where the blackness of outer space is visible and radiation is considerably more intense than on Earth, LaMeres said. "They get to be involved with a real mission," he said.

"I like the magnitude of the impact this could have in terms of cybersecurity," said Brendan Gleason, a senior majoring in mechanical engineering technology and a member of the capstone team. "It's cool to know we're working toward something that could benefit society."

Ultimately, the encryption tool would be implemented in tandem with MSU's radiation-tolerant computer technology, called RadPC, which would oversee the generation and use of the random numbers. Whereas traditional space computers have used oversized circuitry to fortify against the radiation particles, RadPC uses multiple inexpensive processors like those found in personal computers. The processors are programmed to operate in parallel, so that when a radiation particle disrupts one, the others recognize the fault, continue the computation and re-program any damaged computer memory.

One of the final tests of RadPC is underway as a small satellite containing a prototype orbits the Earth. A second satellite test is scheduled for later in 2019. The project has received $2.5 million in NASA funding while supporting hands-on research for more than 60 MSU students, mostly undergraduates, LaMeres said.

More From My 103.5 FM